CHOCOLATE FACTORY: TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION

From the classic period into the mid-eighteenth century, people consumed chocolate as a beverage made from coarsely ground cacao beans and spices—strong, thick, bitter, loaded with fat, and difficult to digest. Manual preparation on a small scale with simple devices made late eighteenth-century chocolate factories resemble little more than overgrown apothecary shops. Then, in 1795 during the midst of the Industrial Revolution, chocolatier Joseph Storrs Fry brought a Watt steam engine into his factory to grind cacao beans, introducing mechanical techniques to the cocoa business. Thereon, inventive men with creative, scientific ideas began to change the taste, quality, quantity, and method of chocolate-making initiated by the Maya thousands of years ago. Streamlined production lowered the cost, while diversification expanded the market. Technological innovations in chocolate processing and diversification between 1828 and 1879 set in motion a chain of events that resulted in modern chocolate production.

A fifty percent fat content made chocolate difficult to digest and difficult to make into solid form—a hurdle Dutch chemist C. Van Houten tackled in 1828 with the use of a mechanized hydraulic press. Van Houten extracted the fatty butter from the cacao bean solids, reducing fat content to twenty-seven percent. His process produced a cacao cake able to be pulverized into a soluble, easy on the stomach, reduced-fat cacao powder. Modern chocolate embraced Van Houten’s machine: in 1847 J. S. Fry and Sons used the machine to produce the first chocolate bar; Cadbury purchased a Van Houten machine in the 1860s to press their own cacao powder, “Cocoa Essence,” a success that launched their long-term success; and Rowntree invested in a Van Houten machine in the 1880s, using it to transform the company from a small family business into a large-scale manufacturer.

Van Houten successfully created powdered chocolate, but he wasn’t satisfied with its bitter taste or solubility. He experimented with treating the powder with alkaline salts, and found they removed the bitterness, varied the color, and allowed the powder to mix more easily with water. His discovery, known as “Dutching,” enabled consumers to prepare mild-flavored Dutch chocolate beverages at home. Modern chocolate consumption increased, and Van Houten’s Dutch process cocoa became a standard ingredient in popular favorites like chocolate ice cream, hot chocolate, and chocolate cakes. When the National Biscuit Company created the Oreo in 1912, they used a heavily alkalized black cocoa powder version of Van Houten’s invention and gave the new biscuit the distinctive color and flavor that made the Oreo the most popular cookie in the world today.

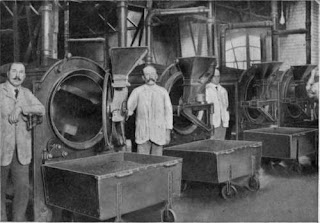

Swiss chocolatier and industrialist Phillipe Suchard was unhappy with the grainy results when mixing chocolate with sugar to remove bitterness in the solid chocolate confections. In 1830, Suchard finally mechanized the ancient hand method of grinding cacao beans on metates. His invention, the melanguer, ground cacao nibs together with sugar using two heavy round millstones supported on a heated granite plate that remained stable while the factory floor beneath rotated forward and back propelled by hydropower. The constant, heated, heavy movement eliminated the grainy texture when sugar and chocolate were mixed. Suchard’s melanguer helped solve the grainy problem, providing a smooth blend when chocolate was mixed with other substances—a critical innovation in modern chocolate manufacturing that remains in use for grinding cocoa paste today.

In 1848, Joseph Storrs Fry, British Quaker and chocolate factory innovator, looked to solve an efficiency drawback Van Houten’s machine posed by removing the fat from chocolate: an abundance of cocoa butter as a byproduct. Fry’s solution innovated a modern chocolate standard. Using Watt’s steam engine technology and the Van Houten press, Fry extracted cocoa butter with the Van Houten machine, then blended the butter with cocoa powder and sugar for better viscosity and cast the resulting smooth paste into a mold. The hardened molded chocolate bar—a portable confection—proved a success in diversification and economic efficiency. Inspired by Fry, Cadbury produced their first chocolate bar in 1849, and modern chocolate followed with over a century of different versions of the portable treat.

Daniel Peter of the Swiss General Chocolate Company was determined to combine chocolate and milk to erase chocolate’s bitter taste. However, chocolate and milk were bitter enemies—the water content of milk and the fat content of chocolate wouldn’t mix to a smooth consistency. The milk caused chocolate to shrink, separate, and disintegrate, and chocolate with milk content went rancid quickly. In 1876 Peter approached his neighbor Henry Nestle, a German-Swiss pharmacist who had experimented with alternate forms of milk for infant nutrition. The formula they came up with successfully combined Nestle’s dehydrated condensed milk with cacao solids and sugar. Peter mixed in additional cocoa butter, chocolate liqueur, vanilla, salt, and more sugar to achieve a sweeter and smoother chocolate that had milk, but because it was dried milk the resulting product didn’t get grainy and had a longer shelf life. The invention of milk chocolate not only supported the local Swiss milk industry, it lowered the costs for chocolate and presented a sweeter chocolate confection. The men’s “Chocolat au lait Gala Peter” became the world’s first commercially sold milk chocolate. Modern chocolate production embraced milk chocolate. Cadbury began mass producing milk chocolate in 1905 and it soon became their best-selling product. Hershey and Ghirardelli followed suit in the US with Hershey’s popular Milk Chocolate Bar and Kisses, and Ghirardelli’s successful Sweet Milk Chocolate bar and Flicks. Different international recipes, like Cadbury’s in England, Toblerone and Lindt in Switzerland, and Baci in Italy, produced unique flavors that made milk chocolate a modern global taste success.

Mechanized production innovations by Van Houten and Suchard improved the capabilities of chocolate production and expanded the horizons for chocolate consumption, but the resulting chocolate was still too lumpy and grainy for Swiss chocolatier Rudolph Lindt. In 1879, Lindt invented a method called “conching.” Adding more cocoa butter to reduce viscosity, Lindt’s shell-shaped machine processed cacao beans for hours with frictional heat to drive out excess water and aerate the mass into a silky smooth chocolate liqueur with reduced bitter and sour flavors, a deeper taste, and enhanced aroma. The resulting chocolat fondant, a “melting” chocolate, could be easily and smoothly incorporated into cake and cookie batters to make sweet treats, while its viscosity allowed it to be poured instead of pressed into molds. Eaten alone, Lindt’s new chocolate melted on the tongue. The smoother chocolate texture and speed of process using Lindt’s conching machine furthered industrialization and contributed greatly to the high quality of Swiss chocolate. Consumption of chocolate soared after Lindt’s 1879 invention, making his innovative conching method so valuable to modern production that, in 1899, Chocolat Sprügli AG paid him one point five million gold francs for his marketing rights and recipe.

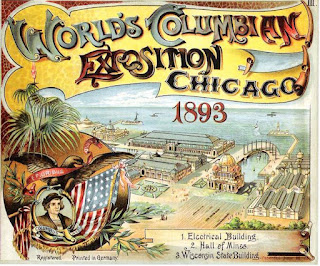

The technological innovations in chocolate processing and diversification created by Van Houten, Suchard, Fry, Peter and Nestle, and Lindt between 1828 and 1879, triggered a chain of events that resulted in modern chocolate production. As it had with other manufacturing sectors during the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution radically changed processing and technique in the chocolate industry. Modern chocolate production expanded in speed, diversification, quality, access, and lower cost as the appearance of large chocolate companies in the US, UK, Switzerland, France, and the Netherlands embraced new machinery and processing methods. Modern consumption, with its new low price and common demand, changed chocolate from a treat for the elite to a confection for the masses.

Bibliography:

Brenner, Joël Glenn. “From Bean to Bar.” In The Emperors of Chocolate : Inside the Secret World of Hershey and Mars, 90–101. First edition. New York: Random House, 1999.

HIS429. Lecture 5. Chocolate Factory: Technological Revolution

Lawrence, Sidney. “The Ghirardelli Story.” California History 81, no. 2 (2002): 90–115. https://doi.org/10.2307/25177676.

Snyder, Rodney., Bradley Foliart Olsen., and Laura Pallas Brindle. “From Stone Metates to Steel Mills.” In Chocolate, 611–623. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2009.

Comments