CHOCOLATE ENCOUNTERS: MEXICAS AND SPANIARDS

The popularity of chocolate’s symbolic and practical uses spread throughout Mesoamerica into the Post-Classic era of the Aztec Triple Alliance and the early sixteenth-century Spanish conquest. The two-way process of colonization gave rise to an important cultural exchange between the New World and the Old World that included the acquisition of new tastes, including chocolate. Spanish victors in Mexico acquired a taste for the chocolate-drinking habit of the Mesoamerican vanquished and needed a discourse to explain their new craving. In order to justify consuming a food of the uncivilized, the Europeans appropriated Mesoamerica’s pre-existing use of chocolate as a medicine.

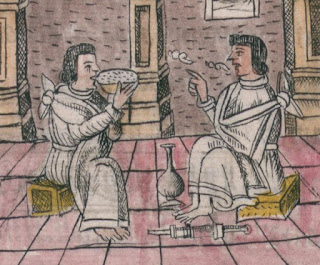

The medicinal use and healing power of chocolate was passed down from the Maya to the Aztecs. Based on a spiritual belief that sickness was God’s punishment, Mesoamerican medical practitioners used supernatural means like astrology to interpret an affliction, and pathological treatment using plants, including cacao, as a remedy. The Aztecs expanded their knowledge of the curative power of plants like cacao through studies in botanical gardens. Mocteczuma I’s garden at Huaxtepec, the first testing lab for medicinal plants, utilized every part of the cacao plant for remedies. Cacao bark, leaf, and flower preparations were used orally to treat skin injuries and irritations. The application of cocoa butter as a lubricant soothed chapped lips—the Mexica version of Chapstick. As a medicine by itself or as a vehicle to dispense other remedies, chocolate helped to aid digestion, stimulate appetite and the nervous system, facilitate weight gain, treat tuberculosis, lower fever, and cure sexual dysfunction. Along with its other uses, chocolate’s medicinal properties and feel-good effect were a major part of Aztec culture when the Spanish arrived.

The Spanish began consuming chocolate, the favorite drink of the “uncivilized” Aztecs, more by chance than desire. Deeply embedded in Aztec custom and culture, the likelihood of Spaniards encountering chocolate was unavoidable. Cortes first tasted chocolate at banquets organized in his honor by the emperor and found the drink bitter, strange, and nearly undrinkable. But Spaniards’ reverse acculturation to chocolate came about in everyday settings. Conquistadors didn’t cook, and the Mexica women they hired as domestics followed tradition and served chocolate at the end of every meal. Conquerors tasted the chocolate drinks Mexica women sold at outdoor markets. Spanish soldiers noticed the spurt of energy indigenous warriors got from the chocolate pellets they carried. In the “Medicinal Herbs” chapter of the Florentine Codex, author Bernardino de Sahagun noted that too much of a chocolate drink was “extraordinarily fattening, in ordinary amounts it’s refreshing, consoling, and invigorating, and in some cases ‘makes one drunk as if it were mushrooms.’” Unaccustomed to stimulants, the Spanish developed a taste for the feeling they got from using chocolate. Once hooked, they needed an excuse and called their usage medicinal.

The pretext of chocolate as medicine crossed the Atlantic to Europe where chocolate and cacao did not exist until missionaries and merchants introduced it after the conquest. A European taste for chocolate didn’t catch on immediately. Deemed disgusting, addicting, and uncultured, sixteenth century Milanese adventurer Girolamo Benzoni wrote that chocolate “seemed more like a drink for pigs.” But because Europe was disease ridden and sought medicines to combat afflictions, a taste for the chocolate’s curative potential emerged. According to historian Marcy Norton, chocolate was Europe’s first introduction to a stimulant beverage, and acceptance of chocolate’s restorative medicinal effect paved the way for coffee and tea. As the Spanish had learned in Mexico, chocolate’s stimulative effect was addictive but there was no turning back. Europeans found ways to rationalize the inclusion of chocolate in their diets. To combat the bitterness, veil the origin, and claim chocolate as their own, Europeans tinkered with the Mesoamerican recipe for the medicinal beverage by adding sugar—the first stage in the colonization of chocolate by Europeans.

The Europeans appropriated the ancient Mesoamerican use of chocolate as a medicine to justify consuming a food of the uncivilized, and in a feel-good prescription for success, the two-way process of colonization became complete. The New World “medicine” transformed the Old World diet. Europe colonized chocolate by changing the recipe. Chocolate colonized Europe by changing the continent’s taste.

Bibliography

Earle, Rebecca. “The Columbian Exchange.” In The Oxford Handbook of Food History, 341–357. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

HIS429. Lecture 2. Chocolate Encounters: Mexicas and Spaniards

Norton, Marcy. “Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics.” The American Historical Review 111, no. 3 (2006): 660–691.

Orellana, Margarita de, Richard Moszka, Timothy Adès, Valentine Tibère, J.M. Hoppan, Philippe Nondedeo, Nezahualcóyotl, et al. “Chocolate: Cultivation and Culture in Pre-Hispanic Mexico.” Artes de México, no. 103 (2011): 65–80.

Orellana, Margarita de, Quentin Pope, Sonia Corcuera Mancera, José Luis Trueba Lara, Jana Schroeder, Laura Esquivel, Jill Derais, et al. “CHOCOLATE II: Mysticism and Cultural Blends.” Artes de México, no. 105 (2012): 73–96.

Comments