CHOCOLATE IN COLONIAL TIMES: CONSUMPTION

Like the Aztecs, Europeans embraced chocolate and its aura of exotic luxury as a marker of wealth and power, and served it in courts, royal palaces, and chocolate rooms in mansions. The pleasurable indulgence of chocolate called for accoutrements to match its status. Europeans claimed ownership over chocolate by upgrading utensils, creating art that depicted Europeans consuming chocolate, and inventing new recipes for chocolate that were shared as gifts or put into cookbooks.

Hard to make and often messy to drink, chocolate preparation called for an upgrade to the utensils and serving pieces to make them presentable to European society. To replace Mesoamericans’ splashy cup-to-cup pouring method of frothing chocolate, sixteenth-century Spaniards invented the molinillo, a wooden utensil that, placed in a chocolate drink, produced froth by rubbing the whisk between the palms. The French took high-end preparation a step further with the chocolatière, a seventeenth-century chocolate pot of silver or gold that combined the pear shape of ancient Mesoamerica gourds with the Spanish molinillo, added an arm on the side for pouring, and a hinged lid with a hole for the molinillo. Depending on social standing, Europeans drank their chocolate from handle-free cups made of pottery, silver, or delicate porcelain. Marques Mancera, the Viceroy of Peru in the 1640s, solved the messy problem of tilted or knocked over cups by creating a small tray called a mancerina with a circular lip in the center to seat the jicara. These new and expensive utensils and pieces used to prepare and consume chocolate symbolized opulence and reinforced the role of chocolate as a fashionable and elite beverage.

Art depicting the preparation and consumption of chocolate in Europe show chocolate as a daily habit and as a luxury delicacy served for prestige. Sixteenth-century European paintings portrayed women preparing chocolate concoctions or breakfasting on chocolate. La Chocolatada, a 1710 baroque illustration in glazed tile, represents a party in Barcelona with chocolate prepared and served to the fashionable. The ceremonial act of serving chocolate to the king and members of the Portuguese royal court was such a privilege that renowned Italian artist Alessandro Castriotto of Naples recreated the scene in a 1720 painting. Part of a large panel of Spanish traditional glazed tiles created by Vicente Navarro, dated 1775, portrays elite domestic servants preparing to serve chocolate in porcelain beakers to the resident aristocrats. Chocolate motifs in art communicated the widespread acceptance of the delicacy in Europe.

To satisfy European palates and taste, new recipes for chocolate were created and circulated in cookbooks or as gifts. Spain added sugar, England added milk, and soon recipes with different spices according to region spread across the continent. In 1668 England, the Earl of Sandwich in his journal shared a recipe for frozen chocolate to use as a gift or luxury. A seventeenth-century apothecary to the Grand Duke of Tuscany added perfume-laden flavors to create delicate jasmine chocolate, a recipe the Grand Duke kept so secret that it wasn’t published until the creator’s death in 1697. English cookbooks in the early 18th century included recipes for hot chocolate with sugar, eggs, rose water, and milk, the basic ingredients of hot chocolate drinks today. Across the ocean in 1727, The Complete Housewife—the first cookbook printed in North America, contained a recipe for chocolate almonds. Having one’s own chocolate recipe was a sign of connoisseurship, and the inclusion of chocolate recipes in cookbooks showed the acceptance, spread, and transformation of chocolate from a primitive drink to a delicacy for the palate of civilized Europeans.

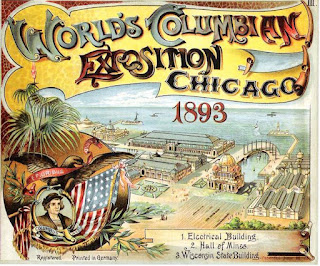

New high-end utensils, paintings and tiles depicting chocolate consumption, and the inclusion of chocolate recipes in cookbooks were ways through which Europeans claimed ownership of chocolate in their culture. The art of serving, representing, and sharing chocolate continues today with items like edible chocolate cups, contemporary and retro art posters of chocolate consumption, and the wealth of public and “secret” chocolate recipes in cookbooks and on the Internet—proof that chocolate has claimed the whole world as its own.

Bibliography:

HIS429. Lecture 3. Chocolate in Colonial Times: Consumption

Loveman, Kate. “The Introduction of Chocolate into England: Retailers, Researchers, and Consumers, 1640-1730.” Journal of Social History 47, no. 1 (2013): 27–46.

Orellana, Margarita de, Quentin Pope, Sonia Corcuera Mancera, José Luis Trueba Lara, Jana Schroeder, Laura Esquivel, Jill Derais, et al. “CHOCOLATE II: Mysticism and Cultural Blends.” Artes de México, no. 105 (2012): 73–96.

Walker, Timothy. “Cure or Confection?” In Chocolate, 561–68. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2009.

Comments